Most stories of alien-human first contact are founded on the underlying assumption that aliens will actually find the human race interesting enough to engage with. In the worst case (very popular in the largely moribund, overblown genre that is American SF “blockbuster” action film these days), that engagement is military in nature—the aliens in these scenarios having apparently decided that blowing us up is worth expending materiel on before they get on with the rest of their nefarious plans for Earth. In the best case, the aliens are friendly and free communication results in good for everyone, thanks to “courageous and dedicated spacemen,” as Ursula K. Le Guin says in her introduction to the new edition of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic.

This assumption is automatically paired with another: that the aliens can communicate at all with humans in a mutually comprehensible fashion. But what if, as Stanislaw Lem imagines in his masterpiece Solaris, the alien beings (or being) is so far removed from human experience as to render any attempts at communication meaningless? Or what if the aliens simply come and go, without even so much as noticing us?

[Read more]

Such is the scenario in the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic. Several years have passed since “The Visit,” when aliens (deduced from certain calculations as having originated somewhere in the region of Deneb) landed briefly on six sites across the Earth, and just as quickly moved on again. The visitation sites, or “zones,” are strange, blasted landscapes, filled with dangerous, invisible traps—”graviconcentrates” or “bug traps” that crush the unwary, and “grinders” that wring out their hapless victims like a wet rag—and with peculiar artifacts and treasures that are worth a lot of money to the right buyer. But the towns near the zones have become blighted—corpses reanimate from time to time, and the children of those who spend much time in the zones suffer terrible mutations.

While many would like to attribute a purpose to the aliens whose visit created the zones, at least one scientist doesn’t see it that way. He posits that the aliens are akin to a group of daytrippers who, after stopping for a picnic, have left a pile of refuse by the side of the road: “an oil spill, a gasoline puddle, old spark plugs and oil filters strewn about.” Humans, he argues, have no more comprehension of the alien detritus than a bird or a rabbit would of an empty food tin.

When we first meet our main anti-hero Red Schuhart, he’s a laboratory assistant at the International Institute of Extraterrestrial Cultures in Harmont, a town that seems to be somewhere in an industrial area of North America, and which is right next to a zone. The IIEC has been established to study the zones, and as a sideline to his day job with them, Red is a “stalker,” a man who has learned how to navigate the zone and bring back its treasures for sale on the black market.

To be a stalker is to be a criminal; it seems at first as if Red might be able to work legitimately with the IIEC, but after a trip into the zone with his scientist friend Kirill goes bad, Red soon finds himself in the classic position of the career criminal who is always hoping for the big score, the rich strike that will allow him quit and to take care of his wife Guta and his mutant daughter known as the Monkey. There is a legend amongst the stalkers of a “Golden Sphere,” an artifact within the zone that will grant any wish—and one day, whether Red wants to or not, he’s going to have to go looking for it. And the wish he brings to it may even surprise him.

The Strugatskys’ novel had a contorted and convoluted publishing history in the Soviet era, described in detail by Boris Strugatsky in his afterword. The authors struggled less with government censorship in the traditional sense as with an institutional objection to “coarse” language, anything deemed to reflect “crude, observable, and brutal reality.” The resulting text was, to say the least, deeply unsatisfying; this new edition, translated by Olena Bormashenko is fully restored to the authors’ original text. I’ve read one other translation, by Antonina W. Bouis, and while I admit the original Russian is beyond me, the new translation seems to convey the original’s spirit more accurately. The language is more original, the phrasings and word choices less awkward.

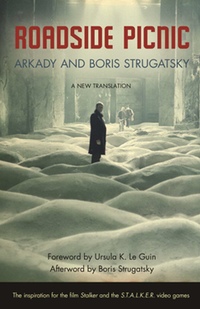

Roadside Picnic is famous not only in its own right, of course, but also as the basis for Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker. It’s one one of those polarizing movies—either you fall asleep out of sheer boredom half an hour in, or you’re mesmerized for the entire 163 minutes, start to finish, and find yourself obsessed with its bad-dream imagery and Slavic existentialism for ages afterward. It’s an iconic film and cannot help but loom large over the novel that inspired it—so much so that the cover of Roadside Picnic is one of the unforgettable images from the film—its three main characters standing in a room lit with a cold white light and filled with humps of white sand.

But Roadside Picnic is a rather different animal from Stalker. Tarkovsky only hinted at the zone’s dangers and wonders through suggestion, the reactions of his actors, and meticulous, vivid cinematography. We see the Stalker throwing metal nuts down a path to determine the safest way, just was Red does in Roadside Picnic, but Tarkovsky never quite spells out what he’s looking for or trying to avoid. We just know from his expression and the way he talks to the Writer and the Scientist that it must be very bad indeed. The science fiction is more explicit in Roadside Picnic—the nuts, it turns out, reveal the locations of the “bug traps”—though the sense of dread is no less.

Still, even though Stalker and Roadside Picnic go about their stories in different ways—the former an epic tone-poem of human desire and strife, the latter something more like a heist novel—they both circle around a powerful metaphysical longing, a yearning to make sense of humanity’s place in the cosmos. The Room of Stalker and the Golden Sphere of Roadside Picnic offer a kind of hope, a vain one perhaps, that Red Schuhart’s final, desperate plea might one day be answered—and suggest that this hope is what continues to propel the human race forward, against the universe’s indifference:

Look into my soul, I know—everything you need is in there. It has to be. Because I’ve never sold my soul to anyone! It’s mine, it’s human! Figure out yourself what I want—because I know it can’t be bad! The hell with it all, I just can’t think of a thing other than those words of his—HAPPINESS, FREE, FOR EVERYONE, AND LET NO ONE BE FORGOTTEN!

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX, and falls into the “obsessed” camp re: Stalker. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.